Annie “Londonderry”

The First Woman to Circumnavigate the World on a Bicycle

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky is already struggling under the weight of patriarchy when two arrogant gentlemen wage a bet that a woman cannot possibly be as physically capable as a man nor able to care for herself as a man can. The wager? $10,000 if Annie can circumnavigate the world in less than 15 months and raise $5,000 in the process.

Eager to prove those “gentlemen” wrong, Annie jumps at the chance, and leaves her family behind for the bike trail – the only problem? She’s never ridden a bicycle before! How on earth will she get around the entire world with just her 42lb bike, a skirt and corset, one change of clothes and a pearl-handled revolver? You’ll have to listen to find out!

“I didn’t want to spend my life at home with a baby under my apron every year.”

“Miss Londonderry expressed the opinion that the advent of the bicycle will create a reform in female dress that will be beneficial. She believes that in the near future all women, whether of high or low degree, will bestride the wheel, except possibly the narrow-minded, long-skirted, lean and lank element.”

Episode Transcript

Annie was born in Latvia in either 1870 or 1871, the daughter of Levi and Beatrice Cohen. They all moved to the United States in 1875, settling in Boston.

Then in 1888 she marries a guy named Max Kopchovsky, who was a peddler, and as most couples do they start having kiddos and by 1892 they had two daughters and a son (Annie was just 21 – if you’re doing the math).

And while we don’t have super inside info on what was going on in her mind, I get the sense, based on the articles I read, that Annie was feeling a little bogged down by all of it. In particular there was a quote of hers in an interview later in life where she said “I didn’t want to spend my life at home with a baby under my apron every year.”

SO THEN ANNIE HEARS ABOUT THIS BET…

As the story goes, there were two dudes in Boston wanted to challenge a woman to an impossible task to prove a woman wasn’t both as physically capable as a man or as capable of taking care of herself so they wagered a bet that Annie couldn’t ride a bicycle around the world. She had to complete the ride in 15 months, and if she did it she’d win $10,000 and she had to raise $5,000 along the way

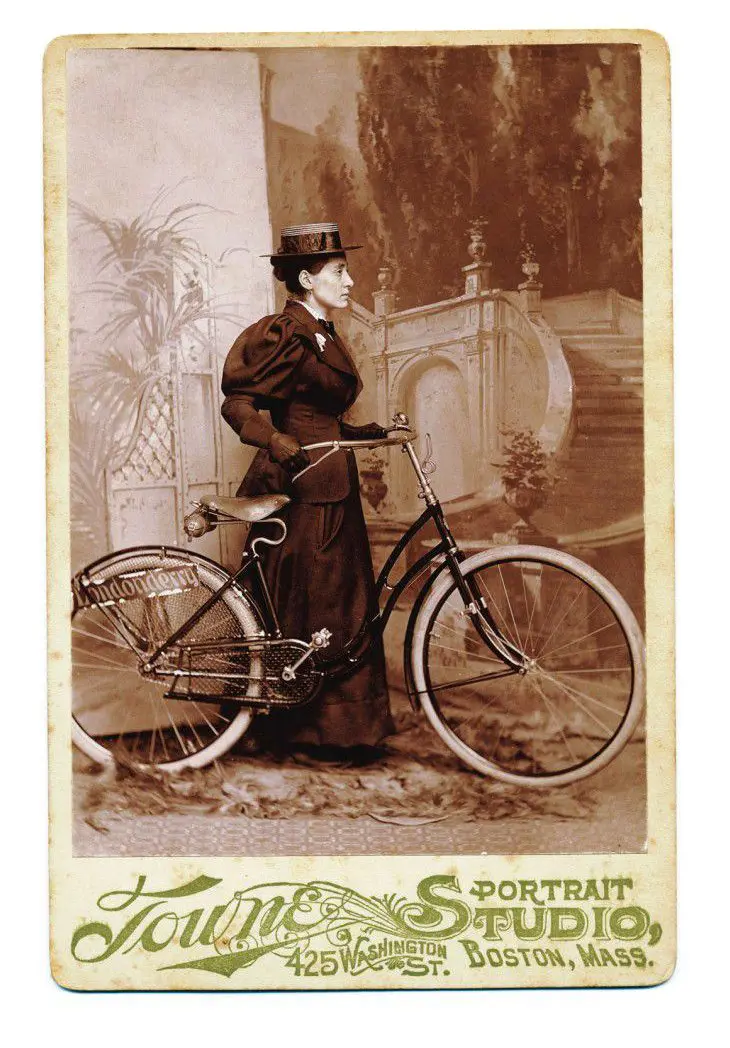

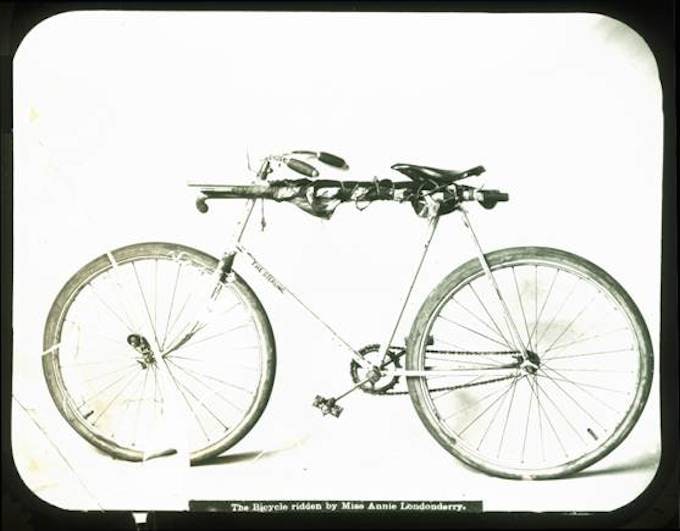

NOW, Annie, who had never written a bike before, was so incensed at THE AUDACITY that she says YES! And on June 27, 1894 Annie Kopchovsky says goodbye to her husband and three small children and, wearing a corset and long Victorian Era dress and carrying a pearl-handled revolver and a single change of clothes, Annie climbs atop her 42-pound women’s Columbian drop frame bicycle with a skirt guard over the rear wheel to keep her skirt from getting caught in the chain, and she begins to ride West towards New York.

Unlike the Tour de France and other famous bike races, Annie rode without any entourage or support team. She stayed at inns or the homes of strangers she met along the way. On some nights she even had to camp.

I’m not clear on whether she had displayed these abilities prior to her trip, but once she was one the road Annie became a total master of self-promotion – I should say – out of necessity – she had to find ways to make money along the way. Her very first sponsor was the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company. They paid her $100 to carry a placard bearing their name on her bike. She also agreed to add the company name to her own – and this is why, if you google her, her name is listed as Annie “Londonderry” Cohen Kopchovsky.

As she went along the road Annie got really good selling advertising placards and ribbons, which she attaching them to her clothing or her bicycle. She also sold her pictures, autographs and mementos souvenirs,

She also gave exhibitions of bicycling and delivered lectures and she would present her robust collection of slides alongside her vibrant stories of what had happened to her along the road.

And some of these crowds listening were HUGE. It turns out she had very cleverly, had alerted to her presence by sending telegrams to local newspapers before she would arrive in the city,

She made the move from skirts to bloomers to a man’s suit during the course of her journey, slowly becoming more comfortable and more of an affront to those who thought the sight of a woman cycling was uncouth.

The Omaha World Herald reported: “Miss Londonderry expressed the opinion that the advent of the bicycle will create a reform in female dress that will be beneficial. She believes that in the near future all women, whether of high or low degree, will bestride the wheel, except possibly the narrow-minded, long-skirted, lean and lank element.”

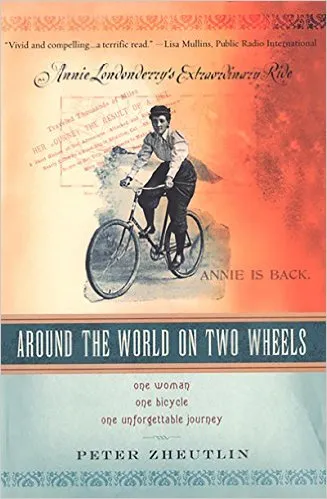

Now, Annie, turns out, was NOT a great natural bicyclist. In his book Around The World On Two Wheels, Peter Zheutlin, says “Annie averaged between eight and ten miles per hour on smooth roads, and a good deal less on poor roads, very slow by modern cycling standards.”

Then, later on in her journey: “It took the more than five weeks to make the four-hundred-mile-stretch to Los Angeles from San Francisco. Had they walked, they could have made it to Los Angeles in half the time.”

That being said it took her three months to make it first to New York (from Boston) and then she gets to Chicago in late September and it was NOT a good time, seasonally speaking, to begin a ride across the great plains

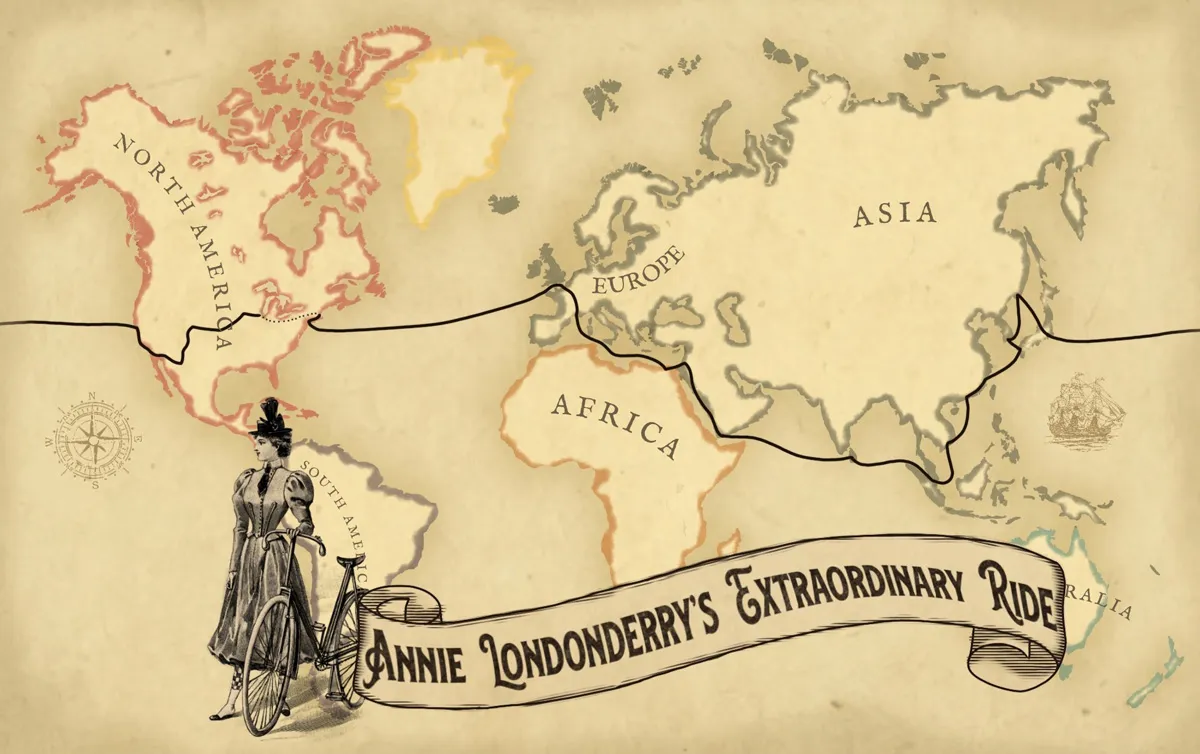

Annie seriously considers abandoning her journey, instead she decides to reverse course, making Chicago the new beginning point – she gets a new, better bicycle, and begins back towards New York and then takes a steamship to Europe (since you can’t bike on the water, of course). There she rode across France (where she was VERY POPULAR, I might add) from Paris to Marseilles before getting on another ship heading to Alexandria, Egypt, on Jan. 20, 1895. There was a crowd of thousands up on the docks to see her off including a drum and bugle corps and a big group of local cyclists. Like I said – she was very popular in France.

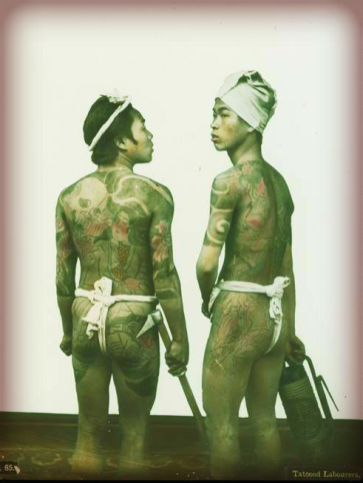

She apparently rides through Jerusalem, then onto Colombo, Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai and then the west coast, riding from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

And she became a global celebrity in the process.

Her big trip was completed in September 1895, and the story of her return was reported in The New York Times. Apparently she arrived with a broken arm from a fall, she said, and had pedaled for hundreds of miles with the injury.

She returned back to her family when the trip was complete, and never again, evidently, made bicycling an important part of her life. She and her husband have a fourth child in 1897, and Annie leaves home again for a time to work as a saleswoman in Ukiah, Calif., about 115 miles north of San Francisco. When she returned, she and her husband lived in the Bronx and operated a small clothing business, which was destroyed by a fire in the 1920s. Apparently they were able to use the insurance money to start another business in Manhattan, called Grace Strap & Novelty, “with a man named Feldman she met at a Horn & Hardart restaurant.”

Then eventually, Annie dies of a stroke on Nov. 11, 1947 at the ripe old age of 77

Peter Zheutlin, In his book Around The World On Two Wheels a bicycle enthusiast and also Annie’s great-grand nephew was intrigued by Annie’s ride – which – several decades after her death, had been kind of lost to time and so Peter dug into a massive pile of research and interviewed Annie’s remaining living relatives.

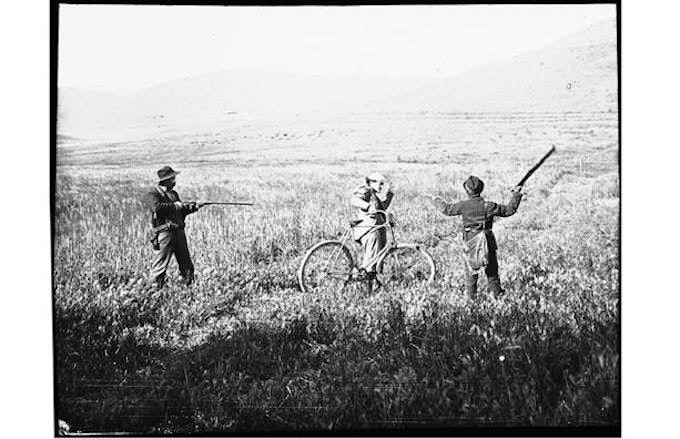

What he discovered is… I’m sorry to tell you… but Annie was QUITE the exaggerator and inventor of great tales.

In her myriad of global interviews she described herself as ALL of the following:

- a Harvard medical student,

- a lawyer,

- a law student,

- an orphan,

- a wealthy heiress

- the founder of a newspaper

- an accountant

She also told widely speculative stories about:

- being waylaid by bandits in France

- hunting Bengal tigers in India

- traveling to the front lines of the Sino-Japanese War and getting shot in the shoulder there

- falling through ice into a river

- ending up in a Japanese prison.

How do we know many of those things probably (or sometimes certainly) didn’t happen?

Well, first of all she spoke quite a lot about her journey through India and China BUT SHE DIDN’T GO THROUGH THERE. She was on a boat the whole time, traversing around those countries on the water.

It’s likely accurate to say that she circumnavigated the globe with a bicycle rather than on one; there is also strong evidence that from western Europe through the Middle East and Asia, from Marseilles to Yokohama, she traveled mostly by steamship.

ALSO, that bet she claimed was the inspiration for the journey? And that she claimed she completed and earned the prize money for? – Well that is believed to be entirely fictitious. The Boston Journal reported: “The crowd [at the State House] were incredulous about her receiving any such sum as $10,000 upon her return. Many expressed the opinion that it was simply an advertising scheme from start to finish.”

Anecdotally, and since it connects to another Broad of ours I can’t resist mentioning – Annie also had apparently written a highly suspect account of her journey which appeared in The New York Sunday World in October 1895 under the byline Nellie Bly Jr. If y’all remember our episode on Nellie Bly – she was the first person to make a trip around the world in 72 days! That was a great episode with our special guest and friend of mine David Blixt.

Well…that’s a lot of exaggeration and lies she told. Kind of a bummer to end the story with that info. BUT IN ANNIE’S DEFENSE, Y’ALL…

It does appear that the first leg of her trip took her from Boston to Chicago, and the last, from San Francisco to Chicago, through El Paso, were accomplished mostly on her bicycle, so it’s safe to say that she definitely was was the first female cyclist to cross the American continent.

And in her journey, she cycled thousands of miles which was MOST CERTAINLY a huge marker in the history of women’s athletics,

Peter Zheutlin doesn’t seem to think Annie was particularly malicious with these tall tales. He says “Annie made her journey out of a desire for fame, excitement and the independence that her conventional societal role had denied her. She loved telling stories, she loved having a story to tell, and she loved representing women as being just as entrepreneurial as men.

“What Annie accomplished with her bicycle in 1894-95 was a tour de force of moxie, self-promotion and athleticism. Though she was a skilled raconteur and gifted self-promoter with a penchant for embellishment and tall tales, she was also, as the evidence, shows, an accomplished cyclist who covered thousands of miles by bicycle during her journey.”

Peter goes on to say “Truly there is no way to measure the impact of her adventure on the larger struggle for women’s equality — to know how many women it inspired or empowered, But Annie’s journey epitomized perfectly the confluence of the women’s movement and the bicycle craze and is, therefore, a small but revealing chapter in the story of women at the turn of the century.”