Loyda Martinez

Fighting for the Rights of Los Alamos, NM

Last week we dove into the history of the land and the hispanos who lived in Los Alamos when the government and Oppenheimer came to town – that’s right the land was not “unoccupied”, as the movie would have us believe. Hundreds of native ranchers and their families were forced off their lands and their livelihoods, and subsequently had no choice but to work at the labs.

TODAY, in part two, best-selling author and award-winning journalist Alisa Lynn Valdés brings us the story of LOYDA MARTINEZ. Loyda’s father was one of the men that was forced off his land and who worked in the labs where him and his fellow locals were not given protective gear, despite the fact that they were working with highly poisonous beryllium. Loyda, who worked at the lab herself, ends up becoming a kind of whistleblower about these real goings on, and for most of her life she’s been fighting tooth and nail for the men and women that worked at the labs not only for recompense from the initial damage but also for better pay and benefits for the employees that suffered at the labs for so long.

With Alisa’s permission, we bring you her episode “The Other Los Alamos Part 2 – Loyda Martinez”, from her podcast CHINGONA HISTORY – uncovering the extraordinary and often overlooked stories of Latinas who shaped United States History. Like, follow & subscribe now to help signal boost Alisa’s crucial new podcast! Find it on:

SPOTIFY or APPLE PODCASTS

Plus any & all of your favorite podcast platforms

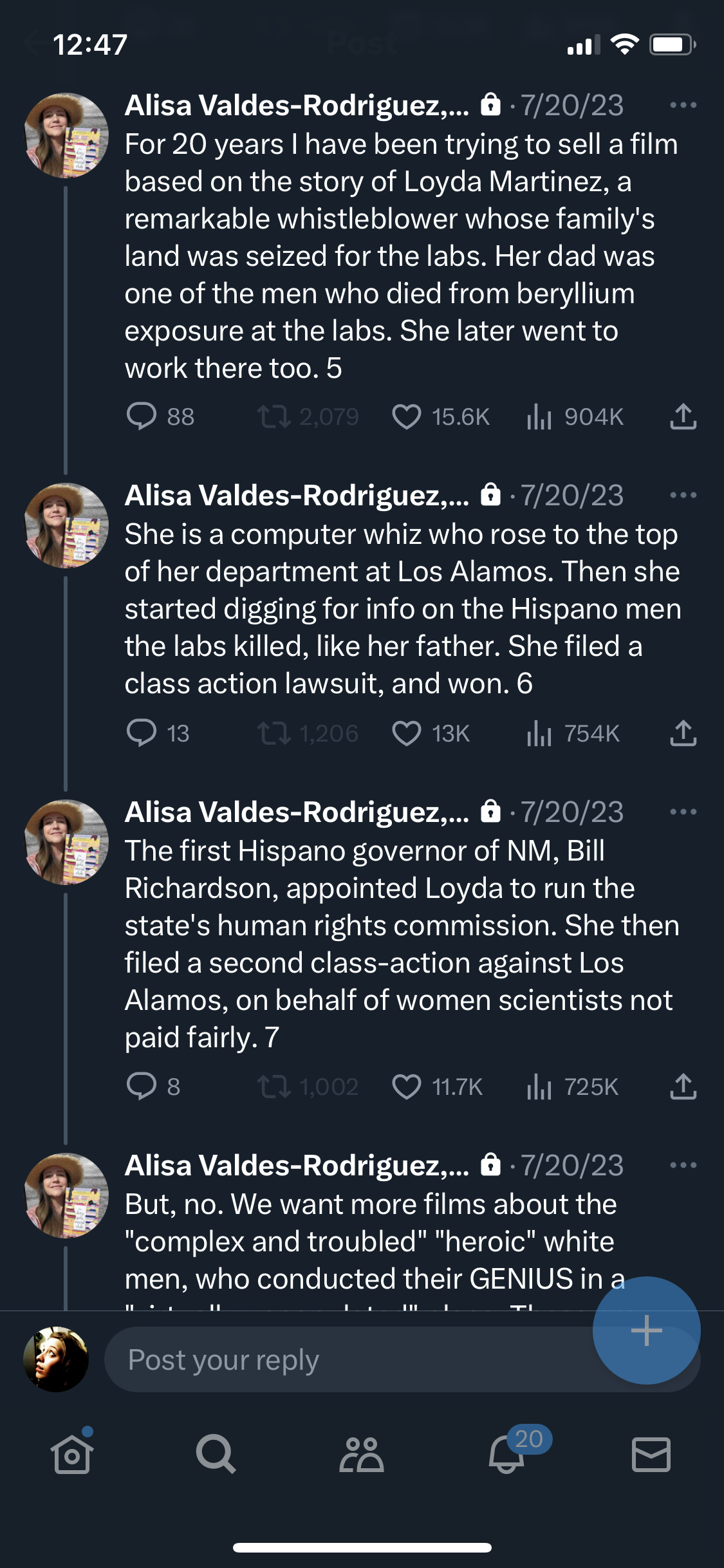

Follow Alisa on Twitter @AlisaValdesRod1

Episode Transcript

Alisa Lynn Valdés 0:01

It has been a couple of weeks now since the opening of Christopher Nolan’s much hyped fictionalized biopic of the real J. Robert Oppenheimer, the film has continued to generate fawning reviews, and plenty of money $439 million worldwide as of this recording. In our last episode, we examined what the film left out.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 0:26

The people who were displaced to build Oppenheimer’s labs in northern New Mexico and upon whom the Manhattan Project later chose to test the world’s first atomic bomb, which was detonated in the southern part of this state.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 0:41

Our special guest today is someone who has seen every stage of the development of Los Alamos National Laboratory in her community will talk to her about how members of her small community were thrown off their land to make leave for the labs, and how our own father was forced to work for the labs in a job so dangerous. It cost him his life. We’ll hear about how the labs worked to try to cover up their fault in his death and incredibly how his daughter grew up to fight back against this massive government entity. Welcome to chin gonna history, the podcast that uncovers the extraordinary and often overlooked stories of Latinos who shaped United States history.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 1:29

I’m your host, Best Selling Author and award winning journalist, Alisa Lynn. Valdés. I’m glad you’re here.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 1:36

Okay. It’s 1998 and Loyda Martinez, a 42 year old computer scientist at Los Alamos National Labs, has applied for a fellowship with the National Hispana Leadership Institute to study at the JFK School of Government at Harvard University. As part of her application, she wrote an impassioned letter which she is here to read for us on Chingona History today.

Loyda Martinez 2:13

“I say as a country, we anguish over the treatment of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. Perhaps this stems from our belief that a civilized nation cannot turn a blind eye to such injustice. Images of families forced from their homes at gunpoint, with little more than what they are able to carry on their backs provides a vivid reminder of a mindset we all hope had ended with World War Two.

Loyda Martinez 2:38

“Americans do not realize, however, that a similar tyranny occurred within their own borders not too long ago, it occurred as part of a national imperative to construct the world’s first atomic bomb, the Manhattan Project in the heart of northern New Mexico, where the US Department of Energy runs the facility now known as El Sol most national laboratory families to were forced from their homes at gunpoint. This is a reality that doe, an elected officials had managed to keep hidden from public view for over half a century. These were the Americans whose lands were taken by force and who deserve our compassion as much as those from other countries who are treated unjustly by their own governments. These are American families who in the 1940s were at gunpoint given 48 hours to vacate their homes. And though assured by government officials, their homes and surrounding lands would be returned after the war that never occurred.

Loyda Martinez 3:37

“These are Americans who are told that they could return over the course of a few days to retrieve livestock furnishings and other personal possessions left behind. But upon returning discovered their homes bulldoze to the ground, personal possessions, troops and livestock set for your shot. In the few instances where there was compensation that was minimal, presumably limited to the value of raw land, loss of livelihood, home water, fences, livestock crops, orchards, furnishings, equipment, and other personal belongings was largely largely ignored.

Loyda Martinez 4:12

“To add insult. While this was occurring, some family members were away supporting the war effort, either as defense workers or as soldiers fighting in Europe or the Pacific. Upon their return, they encountered guards and chain-link fences and a community of new arrivals who are generally biased against them and their families. For these weren’t just any American homesteaders that were driven off their land. These were Hispanic American homesteaders, which perhaps explains why this dark episode in American history is so ignored. That’s why we as Americans ponder man’s inhumanity to men in other parts of the world. Perhaps we ought to take a moment to reflect on the injustice as we allow at home

Alisa Lynn Valdés 4:12

The letter won Loyda that fellowship. And she did a lot of work to set the record straight about what had happened in her community in the early days of the Manhattan Project. It was almost the year 2002. So you would think her employer, the very same Los Alamos National Lab, would have been proud of her happy for her and even celebrated her fellowship. But that’s not what happened.

Loyda Martinez 5:34

Well, in 1999, A lisa, I was chosen for the National Hispanic Leadership Institute, you know that 20 women throughout the country get selected and I was one of them. Now, my references came from back then UN Ambassador Bill Richardson. Senator Polanco from the state of California. Our speaker, Raymond Sanchez, our Senate Pro Tem, Manny had a gun I mean, the lead elected officials in our area, and I was going to graduate, and they didn’t, the deal we put in the newsletter elevated me in their newsletter LANL never mentioned. And if they did, I believe once, it was just very minimal. But I had to pay for my this opportunity. And I had to take my own personal vacation. So I was wanting to take off time to go graduate, we were graduating at the Smithsonian. And they wouldn’t allow me they didn’t approve my vacation. And they told me if I left, I was going to be fired. I made a phone call to our speaker, Raymond Sanchez. He called them our director of LANL. John Brown, five minutes later, call me back and says you’re going have a wonderful trip and make us proud. But I had to go to those lengths, that they wanted to make sure that they did everything possible from the top. Bottom, it was like it was it was a plan. It was orchestrated. They all knew they were all working together. And they knew what to do. It’s it’s just so so the retaliation was so limited, I can’t express it. It was just off the charts.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 7:34

So what was it exactly that the Los Alamos National Laboratory was retaliating against Loyda Martinez for? Let’s go back to the beginning.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 8:02

In 1956, Loyda Martinez was born to Venancio and Margarita Martinez, a couple who had roots in northern New Mexico that went back for centuries. The Los Alamos National Laboratory had been in the area for a little more than a decade by then, and had started to change the way of life in that part of the world. Before the labs arrived, people lived very much as they had always lived in that area. Subsistence farming, not much of a reliance on industrialization or money. And there was very much a Pueblo terroir approach to communal child rearing. Here’s how Loida remembers growing up in Santa Cruz, a small northern New Mexico mountain town, like all of the little towns that surrounded the area that became Los Alamos.

Loyda Martinez 9:08

So, I’ve always said if I had three wishes, one of my wishes would be to live back, live my childhood back, because I live such as simple, innocent life. It was just beautiful. We didn’t have money. But so when it’s snow, we get cardboard boxes and we go to a hill and we’d slide down in the cardboard boxes. We didn’t have money to go to the swimming pool. So we’d had the irrigation ditch the Sekiya Yeah, and we get a shovel and dig out so it could be at least knee deep right and we were small. And then we come out all wet and we put mud all over us. Today you spend hundreds of dollars for one session. We get it all the time, right? But we could go home my mom in the winter would have baked cookies for us or or hot chocolate. It was Always so precious, you know, our hands frozen step. I mean, just a simple life. Our type of crime was we went to the neighbor’s because they had bigger cherries or bigger apples or whatever, are sweeter and so we’d go and steal from them, right? I mean, wasn’t stealing, but it was just cute. It was just so simple. So innocent. Yeah. And today, it’s so complicated. I had beautiful. It was beautiful. My upbringing, it was just so innocent and so pure. I didn’t even know we were poor. And you never felt it. But of course, I always said both of them. That’s one of my wishes. But I’m sure my mom and dad wouldn’t want to go back to those days because they struggled. They worked hard, just to provide for their children. As simple as it was. They provided for us. And we always had food on the table we had, my dad would raise a animal. And then he’d butcher it for the winter. And we’d eat it. There was one lamb. We called him Blackie we he became our pet, but my dad had to kill it. Oh, I know. But it was food on the table. We cried and cried. That was that was the way of life. I mean, it wasn’t like we, you know, things were different. Back then we planted a garden. We ate really organic. We ate beans and chili and to tears every day until my brother came. And then they pull out the pot roast you know the meat for what he came to so that he could eat. Because he too probably more than likely in college was suffering too, right? He wasn’t eating like he wants us to eat. And so I mean, it was tough for my parents. But I remember when my dad might with my dad, he tiptoe back and forth. So proud of my brother when he graduated from high school and he was valedictorian of his class. The my dad just shined. He was so proud of him. What high school was that? Santa Cruz High School. It doesn’t exist any longer. My brother was a basketball player also. And I was a cheerleader. Yeah, so we, you know, we went to all the games together and such. And we went in, in school buses back and then while you still go, but the school bus is so much more sophisticated than they are, you know, back in. Today, they’re much more sophisticated than back when we were we were in high school, but it was just the innocence of a growing up, it was beautiful.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 13:09

It’s not enough to merely say the US government came in threw some farmers off their land to build the labs. What happened in the Los Alamos region of northern New Mexico was in stark microcosm, the journey of human beings, as we have transitioned away from traditional society, to an industrialized one. And here in the United States, to an industrial society that is built almost entirely upon the business of war making. So you had small Hispano and Native American communities who by then shared many of their customs and much of their DNA, living harmoniously and simply off the land in one of the most strikingly beautiful places on the planet. They had been living this way for 10s of 1000s of years and always had enough now dropped into the middle of this idyllic setting is not just some random government facility, but the nation’s first laboratory for creating the world’s first weapon of mass destruction.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 14:39

So consider the contrasts. rural versus urban, traditional, versus modern, spiritual versus scientific, sacred versus secular. And in the minds of the US government at the time, white people whom They viewed as more advanced and civilized and brown people who were treated as subhuman in keeping with the policies of displacement, and dehumanization that began in the mid 19th century, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, and continued to escalate all the way through the Depression era policy of Herbert Hoover, who sought to blame the great depression on Mexicans, rather than to be held accountable for his own terrible policies. So men, like Venancio Martinez, who’d inherited land in the area, who’d been able to raise families and thrive without money, because they still understood how to live from the land. These men and their families are suddenly landless, and destitute, forced to adjust to not just the lapse, but to an entirely new and foreign way of looking at the value of human beings themselves, the value of the land, the value of animals, the value of everything. Industrialization.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 16:31

The concept pioneered by early capitalists like Adam Smith, changed the very foundation of how our species came to understand the concept of work. Smith was a proponent not have balance and harmonious coexistence with the natural world, but have endless growth and surplus production in the name of profit. Why teach a blacksmith to make a nail? Adam Smith argued, when you could create a factory and reduce each worker down to making one part of that nail as fast as possible on an assembly line.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 17:17

Men like Benancio Martinez men who considered the yearly ceremonial clearing of the irrigation ditches to be the work of holy men. Because water was understood to be scarce and sacred. Were no longer able to spend their days solving problems reading the sky, reading the last one with all that was. They were reduced in an instant, and by military force, to cogs in a machine whose sole aim was and remains to kill as many people as possible.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 18:07

So this is the transition period in her own father’s life, during which Loyda Martinez is growing up with her siblings. In this idyllic setting. Her father, goes to work for Los Alamos National Labs when she’s a little girl trying his best to adapt to this new definition of fatherhood, manhood, work value. He goes to work for the labs. But he’s not welcomed by men like J. Robert Oppenheimer as an equal. He’s welcomed as a servant as a low paid laborer who is so disposable that he’s put to work with toxic chemicals like beryllium, with no protective gear whatsoever, even though his white supervisors all had such protective gear when and if they came close to the chemicals at all. Put simply, the labs mistreated Loyda’s father and other workers because there was just this racist belief that such people were inferior. Not as intelligent thought worth protecting. superstition, superstitious, impoverished, uncivilized. But what they didn’t count on was Loyda Martinez.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 20:01

Unbeknownst to her, Loyda Martinez was born as what we would now define a gifted child, as was her brother, and probably her parents too, because gifted kids tend to fall very close on the IQ spectrum to their parents. She went straight to work at the labs. When she was 18. After graduating from high school, she got a job as a secretary. But being whip smart, she immediately recognized that there were other ways to make a living at the labs that would pay her more. So she inquired about being put through school by the lab that was putting other types of workers through their college education. But in her case, they turned her down. After all, she was just a secretary.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 21:04

So Loyda went to night school on her own dime, while working as a secretary at the labs. And she got her Bachelor of Science degree in computer science with a concentration in mathematics from the College of Santa Fe, and then went on to get a Master of Business Administration with a concentration in Management Information Systems. She was promoted. And then the trouble began.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 21:38

Newly armed with her education, which had given her the ability to conduct research, including data analysis Loida began to look into the records at the labs. She was particularly interested in the pay and protection that had been afforded to the local people, people in her community and in her own family who had worked at the labs. as janitors, construction workers, house cleaners, childcare workers in Los Alamos. What she found, blew her mind.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 22:21

Thousands of America’s former nuclear bomb builders she discovered or sick, dying, or already dead because of their exposure to beryllium, radiation, and other poisons. And the government knew about it and did nothing to help. He spot Banos in her own community had labored for decades, often under suffocating secrecy, handling the most hazardous of materials, with lacks or non existent safety precautions as they assembled America’s new stockpile of nuclear weapons.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 23:06

Loyda says many lived a great part of their lives suffering from illnesses caused by beryllium. And those many included her own father. Thus began Loyda’s first fight with Los Alamos and joining together with other community members to lobby Congress to afford the victims of this neglect, some reparation for the pain and harm caused. She was successful. But it didn’t come soon enough for her dad.

Loyda Martinez 23:47

My father and many others, they got sick at that point in time. There was no compensation. My dad died in 1991. There wasn’t compensation till 2000 With all our advocacy, and not only mine, but so many others, right. 2000 Well, the laboratory was still in deadly denial. Yeah, so there was compensation, but to be awarded, the compensation was just terrible. So it took another four years of advocacy for for Congress to tell the Department of Labor to be more compassionate, fair, and timely. So I know in my father’s situation the medical records weren’t readily available.

Loyda Martinez 24:41

Congressman Tom Udall was was involved at that time, he finally got access to the medical records. I No, no. And my father situation, he sent his staff to Los Alamos National Laboratory and Got to go retrieve the medical records and they were in shares. The staff had to look through the medical records. And they were all rat infested. They weren’t, you know, so we started to get access that way. But my father never got my father passed away in 91. He never received compensation compensation, my mother either. And she died approximately 16 months later.

Loyda Martinez 25:34

So, but I have a sister that was diagnosed positive negative because of the dust my father more than likely brought home from a beryllium. Yeah, so they’ve always tested are positive, negative. That mean for Borreliosis? Yes. But and it was suspected that because of my dad went, took his lunch, his clothes, the dust was in his in his culture, he bring it home. Right. And so those those were the hardships.

Loyda Martinez 26:10

You know, when they first diagnosed my father, they said he had COPD, but they wouldn’t let him see any of the medical records. So he died thinking he had COPD, and when he was a teenager, he smoked a little right just like many young teenagers, but never smoked after that.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 26:30

Or until he was a affiliated with the labs. Yes, yeah. Okay. So they’re knowingly lying to him?

Loyda Martinez 26:39

Yes, it’s a company town. And it’s always been a company town. So until our Congress are at that time our congressmen got involved, didn’t they? Did we not have the true access to the medical records, but again, I say they were and sheds, rat infested sheds that are the staff, Tom Udall staff had to go look for them. So that’s when we knew exactly that my father had passed away with a really osis because there was a doctor that documented it, but they put it away. I left in 2008. And I signed a document requesting all my medical records two days, I’ve never received them either. So practices have not changed. Yeah, and maybe some do, but I haven’t personally received my medical records. And why makes you wonder.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 27:40

You would think that after all of that effort, from the advocates and from officials like Tom Udall, and from the United States Congress, and the Department of Energy that Los Alamos National Labs would change. But as recently as 2018. The Department of Energy cited Los Alamos National Labs again, for failure to produce adequate protocols or record keeping, or protective measures for people working with beryllium.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 28:32

As Loyda, and more people of color began to get their education and compete with white upper level workers for the coveted jobs at the labs, the labs retaliated. They began to announce reduction in force, which they said was due to budget shortfall. But when Loida and others looked into that, it turned out there was no budget shortfall at all. They had used the reduction in force as an excuse to fire hundreds of Hispanic and native workers and replaced them with white workers. But, again, they had not bargained on Loida Martinez, and she fought back. She filed two class action lawsuits against the labs for discriminating against Hispanic and Native American workers and for paying women and non white workers less. She won both cases.

Loyda Martinez 29:43

For wasn’t only one lawsuit, I was part of the reduction in force. Then I was also filed a complaint with the Department of Energy for whistleblower status. Right and the class action lawsuit there were two class action lawsuits for the reduction of force And then so just to clarify all that, and the whistleblower complaint involved money, too, I call that institutionalized racism. Yeah. I mean, I can’t think their mindset in but you know, when you start to see the practices and the patterns, well, if you aren’t, you start to understand what’s happening here.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 30:26

Even with the two wins, and the other lobbying efforts that were successful, it was often too little too late for the workers who were affected by the time the reparations came around.

Loyda Martinez 30:42

So by that time, so many people had passed away, some got their jobs back. But they didn’t receive the medical benefits or the years of service. And so they started at year one. So their pensions, basically went out the window, right, and their medical insurances. And let me just go on and on.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 31:12

After my tweet about Oppenheimer, the film ignoring the spinal and native and rural population of New Mexico went viral, with mention of Loida in it, many media outlets in the US and around the world jumped on the story, including one wire service who ran a story that they believed the reporter told me this was balanced, because they had also spoken with local Hispano families who had nice things to say about the labs because the labs were putting their kids through college or offering them internships and jobs. What that reporter didn’t realize is that it’s not balanced, to tell Loyda’s story, and then say, “but other people see it – see the labs as not being so bad”. When if he had dug a little deeper, he would have found out the only reason those programs that those parents are complementing exist is Loyda Martinez, and her advocacy.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 32:41

She specifically asked for those things.

Loyda Martinez 32:46

So when one time that I was in DC, I met with Senator, Senator Glenn Domenici, Senator being a man Bill Richardson, Congressman Bill Richardson, and Senator Domenici was a very powerful Senator back then. And he tells me literally tells me, what is it going to take for you guys to shut up?

Alisa Lynn Valdés 33:11

And Loyda, were those his exact words?

Loyda Martinez 33:14

Yes. And I, I looked at him and I said, Well, what do you have to offer northern New Mexico. So at the end of the day, what happened was, the LANL Foundation came about that first year, every student that applied to be an intern at the laboratory got hired, that was the first time ever, and then other programs speak because began to evolve. But it was because of this advocacy is why all this happen. They won’t admit it. But I know that because I had the conversation with them. That’s what they offer. And but of course, it still didn’t stop us, because it was just so much more. They had to compensate the homesteaders, they have to compensate the people that were sick, but they may they were, you know, lateral was such in deadly denial. It was like pulling teeth. And then the Equal Pay Act. Oh, my God, why didn’t they pass like others, we finally got a copy of all the salaries. And what we say, at that point in time I wish that I hadn’t even had the education behind me is that I knew how to do the math. And I saw all the injustice is on our salaries, and I thought, oh my god, maybe it would have been better than I didn’t know this. But now that I do know it, that it’s upsetting. How can we survive and have, you know, be respected? I mean, all these rich NGOs that came in for the Manhattan Project, Phil moved to Santa Fe. Lots of money that could happen to Sam pay today, the Hispanics that live in the outskirts, and that you can’t even afford to live in Santa Fe.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 35:18

Loyda really made me think about the way that Hollywood not only ignored the history of what was going on there, but also what’s happening now. Even though you’ll find the occasional TV series now about urban gentrification, and he spinales embodiments. Nobody is telling the story of rural gentrification at the hands of organizations like the Los Alamos National Labs, that makes sure that only a certain kind of person can afford housing and other basic necessities in that area, by paying those people more for the same work than they pay darker people and women.

Loyda Martinez 35:58

That’s going to happen to us too. And Chimayo you should see all people coming from outside here, let’s eautiful place it is. But many families are selling their property because they’re poor, maybe can’t even pay their taxes.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 36:26

Loyda chose an early retirement, rather than continuing to beat her head against the walls of injustice at Los Alamos National Labs. She and her high school sweetheart husband, Fidel, now spend their days on the chili farm that’s been in Fidel’s family for many years that he spinal and Native American communities that surround Los Alamos National Lab now are mired in some of the worst poverty and generational trauma problems in the entire world. Many people who tried to figure out how to solve the problems of poverty and drug addiction and hopelessness, in our region, love to point to education as the key to getting out so that people can get good jobs at places like the labs. But nobody is looking to the past to see what might have been lost. For all of us. No one’s looking at traditional society as having solutions to these problems. This isn’t to say education isn’t important, or a job isn’t important. Our work isn’t important. But it is to say, maybe here and everywhere. Human society needs to start to look to the past. To re think the notion of worth the value of human beings, the land, and the animals and the wisdom or lack thereof of in putting all of your education to work making weapons to destroy yourself and others.

Loyda Martinez 38:41

But what my education did to me was it just made me a lot more smarter to understand what was happening around me. And I’m saying it’s so wrong. Right? Maybe I should have not gotten my education so I could just pretend that nothing was happening and I could escape now.

Alisa Lynn Valdés 39:01

I think the Oppenheimer film tries to grapple with what has been lost. But it fails to do so. Because it does not look beyond the man who created the bomb himself for the answer. The story I’d like to see deals with the native communities into which the Manhattan Project inserted itself as being every bit the equal of the people who came and perhaps having answers and solutions to the problems that plague us now. If only we would listen. This has been Chigona History. I’m your host, Alisa Lynn Valdés I’m also the engineer, the researcher, the producer, everything. It’s just me. I’m glad you’re here.